A TRAVEL THROUGH TIME: Riverside Park

by Janice Anschuetz (2016) ~~~~~

If a city has a heart, then Ypsilanti Michigan’s heart must be Riverside Park. Nearly everyone in Ypsilanti and beyond can share a wonderful memory of an event in the park, whether it is of the 150,000 people from far and wide who participate in the Color Run, those that imbibe in their favorite brews at the Michigan Beer Festival, the thousands who come from all over the nation to the annual Elvis Fest, families that enjoy a Memorial Day weekend concert by the river, car fanatics that attend the many auto shows, those that enjoy meeting friends and family at the Heritage Festival, or the many locals who enjoy their time merely walking the lovely trail by the river in all seasons. Going further back in time you may remember going to the winter Festival of Lights show complete with horse & carriage rides, or having your heart stopped as the Wallenda family replicated the dangerous seven-man pyramid in Riverside Park decades after their family’s tragic accident in Detroit.

The recently-installed Heritage Bridge allows those with wheelchairs, strollers, and bicycles – as well as pedestrians – a Michigan Avenue entrance to the park

2016 is a special year for Ypsilanti’s Riverside Park, located on the Huron River between Michigan Avenue and Cross Street. The recently-installed Heritage Bridge allows those with wheelchairs, strollers, and bicycles – as well as pedestrians – a Michigan Avenue entrance to the park. This is a dream come true after more than 100 years of waiting. The Olmsted Brothers (the landscape firm responsible for plans for Belle Isle, New York’s Central Park, and many other public parks and private gardens) suggested in their 1913 plan for Ypsilanti that the city acquire all of the land adjacent to the river, and even provided an illustration of what is now Riverside Park connecting to Michigan Avenue by way of a bridge. The Heritage Bridge also provides a gateway to the new Border to Border Trail which continues south of Michigan Avenue and becomes a new linear park that connects with Water Works Park, North Bay Park, and Blue Heron Park, and eventually all of the way to the Wayne County line.

Like me, you may have wondered how this beautiful park came about and I would like to share what I have learned of its history. Pretend that you are pausing with me for a moment on the new Heritage Bridge, crossing the Huron River at Michigan Avenue and look back to the charming vista of what is now Riverside Park. Then let us imagine that we can go back in time over two hundred years. What we would see then? High on the northwest bank of the river would be an Indian trading post owned by three Frenchman: Gabriel Godfroy, Fancois Pepin, and Romaine La Chambre which was called “Godfroy’s on the Pottawatomie Trail.” This trading post was built where the Saulk trail (now Michigan Avenue) and Pottawatomie trail (which ran along the Huron River) converged. The post was in a good location as the last trading post before entering the large settlement of Detroit, and the first trading post after leaving that location.

Most likely the trading post would have been a rough hewn square log structure. Perhaps some customers would be lounging in front or camped by the shore of the river. The three major tribes using both the trails and the river for transportation were the Ottawa (Odawa), the Ojibwa (Chippewa), and the Pottawatomie who had formed an alliance know as the Three Fires. The Wendat (Wyandotte) Indians also traveled through the area. The Huron River is said to have been named by the French who thought that the Wyandotte Indian hair style of shaved sides and stiff hair in the middle reminded them of the spine of a wild boar – which they called “huare” and which eventually was anglicized as “Huron,” according to Charles Chapman’s History of Washtenaw County, Michigan published in 1881.

Like other trading posts of the time, we can imagine that Indians, trappers and hunters could exchange the fur of beaver, deer, bear, fox, wildcat, wolf, otter and muskrat for powder, shot, muskets, cast iron cooking pots, axes, knives, beads, silver breast plates, bracelets, and other items.

If we could go back over 200 years we would see high on the northwest bank of the river an Indian trading post called “Godfroy’s on the Pottawatomie Trail” after Gabriel

Godfroy.

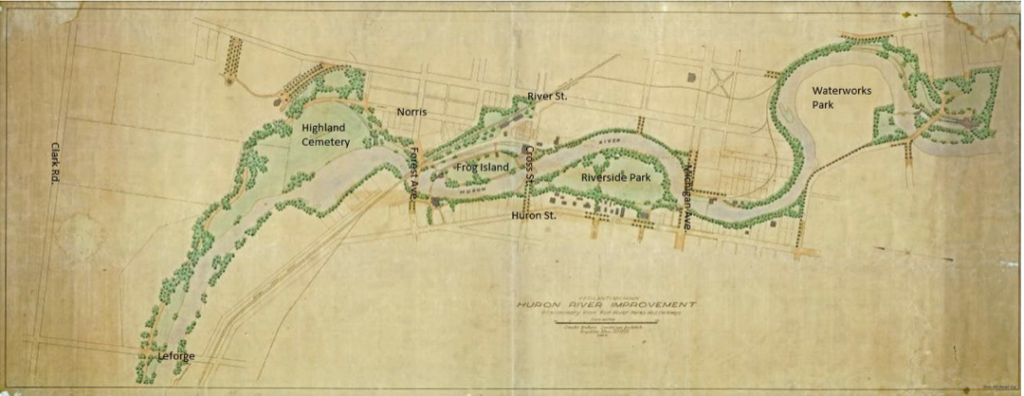

In 1913, the Olmsted Brothers were commissioned to give advice on how to help the town grow and to provide a healthy living environment for its citizens.

We learn more about Colonel Gabiel Godfroy in The Story of Ypsilanti written by Harvey C. Colburn, published in 1923, and now available for sale in re-print at the Ypsilanti Historical Museum Archives. Godfrey was a man of influence and ambition as well as some wealth. Like his partners, Pepin and La Chambre, he was not a friend of the British and supported the Americans in the war for independence. He was 51 years old when he established the trading post in 1809 and, like his partners, was firmly established in Detroit where he held office as an assessor, operated a ferry across the Detroit River to Canada, and owned a milling business. It seems that he continued to live in Detroit while he owned the trading post, and he also owned 68 acres of land in Detroit and another 200 acres in Dearborn. Along with his son in law, James McCloskey, he served on the Detroit Board of Selectmen, on which there were only five members. We know that in 1814 Godfroy was one of the trustees of historic St. Anne’s Parish (the 2nd oldest continuous Catholic Church parish in the nation still in existence) and that by 1815 he also owned a tannery in Detroit. His commission of Colonel is from the First Michigan Regiment.

His partners, Pepin and LaChambre have also left their mark on history by supporting the Americans instead of the British. In fact, at one time, a British officer, Colonel Burke, wrote a letter to the Pottawatomies in an effort to turn them against the Americans, and the letter fell into Pepin’s hands. Pepin made sure that the message was delivered after he added this postscript: “My Comrades: You know that I have always spoken to you as a brother and this time I am incapable of lying to you. He who writes this (Burke) is neither a Frenchman nor a priest, but a rascal who has been chosen by the English to deceive you.”

The trading post did not last long. It burned and was rebuilt once but the treaties of Detroit and Saginaw removed the Indians from the area. In the year 1811, these three ambitious men took advantage of the new opportunities for land ownership in what would become Ypsilanti, and purchased large tracts of land in the area known as “French Claims”. The claims began at the river and then followed the line of what is now Forest Avenue southwest for about two miles and then the line turned southeasterly for two miles again where it intersected with the river. This area composed about two square miles, or around 2,500 acres, and the river became the eastern boundary. The deeds were signed by President Madison along with the three Frenchmen who partnered in the trading post. Two of Godfroy’s children also shared in the ownership.

By 1823, the river, and the water power it offered, was quickly bought up by nineteenth century industrialists such as Norris, Harwood, Hardy and Reading, who all built dams for harvesting the river power. When the railroad was built in Ypsilanti in 1838, stockyards holding sheep, pigs and cattle lined the river bank. Far from the clear waters we see today and could imagine when the trading post flourished, looking down from Heritage Bridge we would have seen waste – both human and animal – and garbage of all descriptions – flowing in the river, certainly no place for a tranquil park.

The Godfroy family sold their land on the river to some of the wealthy industrialists who had taken advantage of the river power, before the age of electricity. Soon elegant and picturesque mansions lined the high banks of the Huron River, many with ornate terraced gardens which lined the sides of the cliff. Because the river often flooded, the lower part of their property could not be built on, and without stable banks would be considered boggy and marshy – what today we know as wetlands and were then called “flats.”

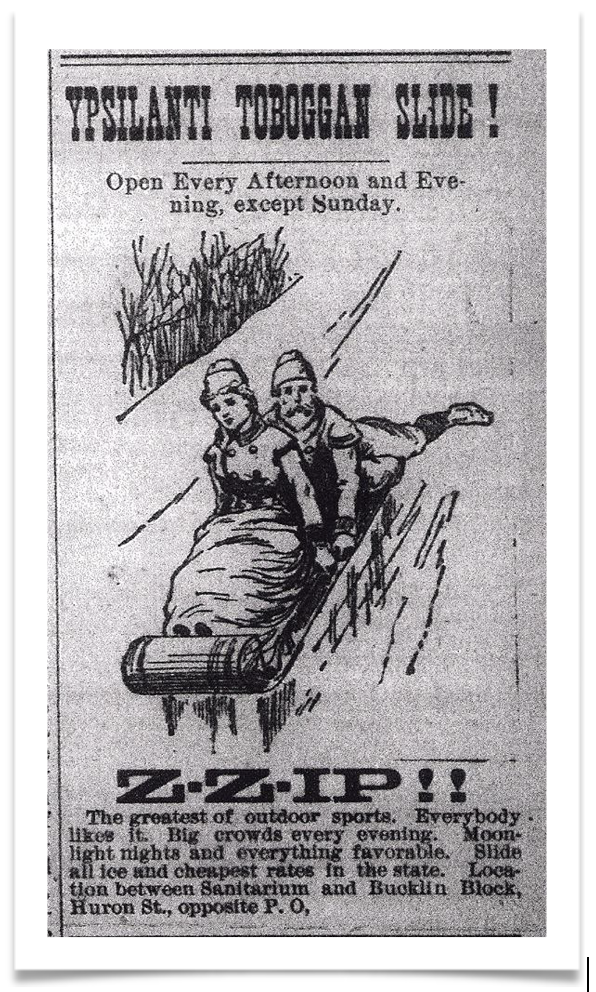

It could be that the first recreational use of this land occurred in 1886 when the Ypsilanti Toboggan Slide Company was formed by four young men. A 200-foot wooden slide was constructed starting at the second story window of an existing barn on Huron Street (about where Riverside Arts Center now exists) and in trestle like fashion with a drop of 50 feet. The wooden structure was packed firm with ice from the river. Thrill seeking Victorians could provide their own sleds or rent one for a modest fee. It seems that this was a spectator sport as much as one for participation, as an audience could watch women and girls in long dresses and men and boys screaming past them as they made the chilling descent from a second story window high above the river.

By 1892 the city formed an official Ypsilanti park system when a group of women determined to transform public land into a park where a cemetery existed at Cross and Prospect Street. The original bodies had already been moved to Highland Cemetery. The land was soon transformed into a pleasant place to walk with flowered paths and even a pond and fountain known as Luna Lake. Visitors were said to arrive by train from Detroit and Ann Arbor to enjoy this tranquil space.

The following account could have been the inspiration of the beginning of a park on the river. About 1908 the Quirk family donated their large Victorian mansion to the city of Ypsilanti for use as a town hall, replacing the small town hall/jail located on the north east side of Cross and Huron Streets. Not only were the residents of Ypsilanti given a stately building, but it came complete with terraced gardens and riverside land. A “Landscape Design for Development for Quirk Park” was done by the Monroe, Michigan firm of J. Joseph Poleo and shows a meandering series of garden paths between the mansion on the bluff and the river. Harvey C. Colburn indicated in his book, The Story of Ypsilanti, that the flats behind the city hall were used for “pageants” and athletic events for the nearby high school. The rest of the area, which is now Riverside Park, was held in private hands with the “ribbon lots”, extending in the French way from Huron Street to the river.

In 1913, the Olmsted Brothers were commissioned by the small town of Ypsilanti, whose population was then about 6000, to give advice on how to help the town grow in such a way as to not only attract business and industry, but to provide a healthy living environment for its citizens. As far as the Huron River was concerned, the Olmsted Brothers were frank in their criticism of its neglected and defiled state saying in their report: “The Huron River with its large natural reservoirs and its steep channel, was long ago claimed for economic uses, by water power development in a small unsystematic way. Many mills were built but most of them have since fallen into disuse and decay, and the river is now largely in a picturesque state of neglect. Its shores now overgrown in many places, pools and rapids break into monotomy (sic), while railways and public roads cross and recross it in many places.”

The report went on to chastise the city for neglecting the riverfront, which at that time was often used as a garbage dump with raw sewage, waste products, and chemicals flowing into it daily. The report continued: “The river, with its many advantages as a naturally beautiful feature of the city, is now almost wholly ignored, or worse, it is defiled and treated as a menace to adjacent property.” The Olmsted Brothers suggested that the flood plain between Michigan Avenue and Cross Street, unsuitable for building, could be used as a public park. The firm also provided a drawing of a string of parks throughout the city on the Huron River, which included what would become Frog Island and Riverside Park. In a more detailed drawing of Riverside Park there is an access bridge from Michigan Avenue in the vicinity of where the 2015 Heritage Bridge is newly located!

About 1908 the Quirk family donated their large Victorian mansion to the city of Ypsilanti for use as a town hall.

In 1932 the house at 126 North Huron Street (shown in this 1908 photo with Mrs. Harrison Fairchild) was purchased by the city and demolished in order to provide an entrance to the park between St. Luke’s Church and the Ladies Library.

Perhaps with the need for employment during the Great Depression of the 1930s and the possibility of municipal projects funded by the Federal Works Progress Administration, Olmstead’s ideas began to take shape. During this time, the city was able to collect the deeds to the many parcels of land that now make up the 14 acres of what we now know as Riverside Park. Some were purchased and some were donated. We read in an Ypsilanti Press article in 1932 that the Detroit Edison Company not only donated the hill and land to the river behind their property, but paid for the land to be landscaped to conform to the adjacent slope and land of the park. The city purchased the old Greek Revival home at 126 North Huron Street and demolished it in order to provide an entrance to the park between St. Luke’s Church and the Ladies Library. We read descriptions of this entrance to the park, which sound charming, involved rock gardens along the slope on the way to the park, and remnants of them can still be seen.

With a polluted river running through it and the river bank still being used for trash and garbage disposal, Riverside Park was nowhere near the scenic refuge we all enjoy today. With movement to clean up the river in the early 1980s, Riverside Park started to resemble the beautiful landscape we now enjoy. Even in the early 1970s, I viewed the river every day when I drove my husband to work at Eastern Michigan University, in our $45 VW Beetle. As we crossed the river, it was always interesting to see what color the river would be – red, purple, green, or brown. This ongoing color change was caused by chemicals from the upstream paper company being discharged into it. Because few families and children used the park for picnics and pleasure, it gained the reputation as a dangerous place to be. Motorcycle gangs were known to use the land behind City Hall as a place to race their bikes up and down the terraces after dark and drug activity could be observed. I remember one day in the 1970s, resolving to bring my young family of five children to the park, that we had to stop as a man, during the heat of an August day, dressed in a long fur coat, made dog-barking noises at us when we passed him by the river. Thankfully those days are now but a distant memory with the beautiful park that we all now enjoy.

Ypsilanti is a town of optimists and hard working generous volunteers and during the past 30 years citizens have joined with city leaders to reclaim the park and help form it into the enjoyable river vista that it is today. Clean water practices have all but stopped chemicals, pollution, and garbage from spoiling this waterway which is now deemed a “Natural River” by the DNR. Over this time, new paved walkways have been added, a bathroom building was erected, new light fixtures and electrical outlets were installed, and a beautiful cement stairway was built that now provides an entrance from Huron Street near the Riverside Arts Center. A gazebo and fishing pier now also grace the waterfront. The “tridge” connects the park to both Depot Town and adjacent Riverside Park. Fishing habitats have been established, and the river itself is part of the new 100-mile waterway which can be enjoyed by paddling enthusiasts.

As you enjoy your next visit to the park – whether it be to an auto show, Elvis Fest, or the highly popular beer fest, or merely through a casual walk, please take a moment to appreciate the many changes that have occurred in these few acres. I hope that this little journey through time has provided you with an understanding and further appreciation of our beloved Riverside Park – which is truly the heart of Ypsilanti.